One of the biggest changes to the Ventura River ecosystem came with the influx of settlers in the 1800s. Some say the oak woodland that filled the valley was so dense that a squirrel could travel in the canopy from Ojai to the beach in Ventura without touching the ground. But as people moved in, land was cleared to make room for agriculture with the wood exported to the growing city of Los Angeles, much of it to be burned as firewood.

As the oak woodland was replaced with irrigated agriculture the water balance shifted from abundance to deficit. Rather than capturing and infiltrating rainfall, the land now required that water be pumped from the aquifers to sustain crops and orchards. By 1890, over 4,000 acres had already been deforested. Today there is approximately 6,000 acres of irrigated land in the Ojai Valley.

Recognizing the importance of maintaining and restoring the remaining oak woodlands, the County of Ventura and other jurisdictions throughout California have ordinances protecting oak trees. Many organizations work to educate residents and coordinate volunteer efforts. In the Ojai Valley this includes;

Once upon a Watershed celebrates OAKTOBER, Oak Awareness Month.

Join OUW and other organizations and individuals across the state and country as we recognize the importance of oaks and oak ecosystems. Every individual, organization, and community can play an important role in celebrating oaks and oak ecosystems throughout the month of October—OAKtober!

Ojai Trees is an Ojai Valley community forestry group that welcomes people of all ages and backgrounds who want to do something tangible to help the environment.

The following are excerpts from publications documenting the history of oaks in California:

Meiners Oaks

http://ojaihistory.com/he-got-meiners-o-for-unpaid-debt/

John Meiners, native of Germany, had come to the United States about 1848 and had established a successful brewery business in Milwaukee. He acquired this Ojai ranch in the seventies, sight unseen, as a result of an unpaid debt. When he heard that his friend, Edward D. Holton, a Milwaukee banker, was going to California for a brief trip, Meiners asked him to see the property he had acquired. Mr. Holton’s evaluation was perhaps it was the largest oak grove on level land in Southern California, much of it so dense that the ground was in continuous shade. Furthermore, to his surprise, Meiners discovered that the climate of the valley was good for his asthma.

|

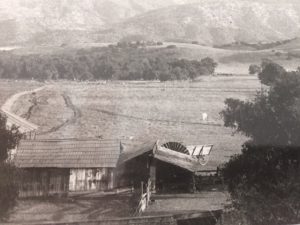

The barn and livestock area on the Meiners Ranch.

A fence surrounds the main oak grove seen in the distance.

Ojai Valley Museum |

Oaks of Southern California

https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/the-oak-trees-of-southern-california-a-brief-history

When Europeans arrived, they noticed the beauty of the oaks and used them as a way to make sense of their novel surroundings. Upon summiting the Sepulveda Pass and looking out over the San Fernando Valley in 1770, a Spanish expedition called the expansive plain Valle de Santa Catalina de Bononia de los Encinos. ("Encino" is Spanish for live oak.) In central California, a later expedition named a oak-shrouded pass El Paso de Robles. ("Robles" referred to the area's valley oaks.) Later, as highly visible landmarks, some trees served as boundary markers between ranchos, appearing on diseños that recorded Spanish- and Mexican-era land grants.

But almost as soon as the Spanish enshrined the oaks in the region's place names, the more intensive uses of they land they introduced began to threaten the trees' survival. Farming, annual husbandry, and the arrival of non-native annual grasses stymied oak reproduction. Mature oaks were cut for lumber or fuel.

American land use practices only intensified the destructive processes. Like their Spanish predecessors, Americans would name their communities and streets after the trees (Thousand Oaks, Fair Oaks Boulevard, etc.) and then proceed to hasten their downfall. Because of the irregular shape of their trunks, oak trees were rarely felled for lumber, but oakwood came to be prized as fuel. The dense wood and lack of resin meant that the wood and resulting coals burned long and slowly.

Just as they had sustained Southern California's indigenous peoples, oak trees nourished residents of the booming city of Los Angeles, albeit in an indirect and unsustainable way. Demand in Los Angeles for hardwood drew loggers into the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and San Gabriel valleys. As the loggers clear-cut thousands of acres of oak woodlands and savannas and delivered the firewood to Los Angeles, bakers tossed the wood into their ovens, feeding a city while denuding the countryside.

Oaks also fell to the axe as Southern Californians envisioned more profitable uses for oak-dominated landscapes. In the nineteenth century, citrus growers cleared oaks savannas to make way for orchards. Other oak habitats declined as groundwater pumping lowered the water table. Later, real-estate developers uprooted trees to build new houses and commercial properties for the expanding metropolis.

A Brief History and Guide to California's Native Oaks

http://www.ourcityforest.org/blog/2020/7/a-brief-history-and-guide-to-californias-native-oaks

The native oaks of California once dominated the landscape. Accounts of Spanish explorers mention their awe at the sight of the abundance of oaks around them. However, those with the strongest connection to the oaks of California were and are indigenous people.

Unfortunately, the arrival of the Spanish did not bode well for the native people nor the oaks of California. The Spanish introduced grazing animals and felled oak forests to make room for their agricultural enterprises. They also saw value in the lumber of oak trees, leading to even more deforestation. Before the native people could do anything to prevent them, the Spanish had dramatically damaged the relationship between the people and the oaks.

The people native to Santa Clara Valley are known as the Ohlone, which is a name that encompasses 50 separate tribes ranging from the South Bay all the way down to Monterey. Native oaks of California are ingrained in their society as a resource both physically and spiritually. Acorns were the primary food source for the Ohlone prior to the arrival of the Spanish and were held in high regard amongst the native people. Anthropologists estimate 75% of native Californians relied on acorns in their daily diet. Their new year, a joyous occasion, was marked by the acorn harvest. The Ohlone people would dance amongst the oak groves each year to promote a good harvest. During the acorn harvest, entire families would go out and collect the acorns of a large tree, which took about a day. The women would then prepare the acorns by shelling them and using a mortar and pestle, grinding the acorns into a fine powder. After being ground, the acorn flour would undergo the lengthy process of leaching the bitter tannins from the acorns which made them unpalatable. After the tannins were leached, the acorn flour was much sweeter and easier to eat and could be used to make soups, mush, and even bread (I myself love acorn bread). Excess unground, shelled acorns could be stored up to 10 years. The preparation of acorns was not just fulfilling a necessity. It was also a time for social connection during which the women could talk amongst themselves and share stories of their lives and even gossip.

The Powerful Survival Story of California’s Oaks

https://marinmagazine.com/feature-story/oak-stories/

The story that oaks tell about the impact of humans in California is mostly a sad one. Natural landscapes dominated by oak trees once covered more than a third of the state. Starting around 1850, clearing trees for agriculture and grazing decimated vast oak lands, and a century later the subdivision boom inflamed a trend that has never really ceased. Biologists now estimate that more than a third of California’s original 10 to 12 million acres of oak woodlands have been lost since settlement, and only about 4 percent of the remaining woodlands are protected. When oaks are lost, so are many of the wild creatures and other plant life that are part of the oak’s rich natural web — among the most biodiverse of the state’s ecosystems.

ACORNS: TRADITIONAL FOOD STAPLE

http://www.danielnpaul.com/CaliforniaNativeAmericans-Acorns.html

As late as 1844, when explorer John C. Fremont led an expedition to the Sacramento Valley, he described the north state foothills as "smooth and grassy; [the woodlands] had no undergrowth; and in the open valleys of riverlets, or around spring heads, the low groves of oak give the appearance of orchards in an old cultivated country." Similarly, a nineteenth-century visitor to the middle fork of the Tuolumne River near Yosemite Valley found it "like an English park-a lovely valley, wide and grassy, broken with clumps of oak and cedar."

Fires were used to insure good growth and healthy orchards:

Natives may have been setting fires for 5,000 years speculates Kat Anderson (an ethnobotanist with the Amerindian Studies Centre at UCLA), judging by how long fire-loving giant sequoias have been expanding their range.

The History of Oak Woodlands in California, Part II: The Native American and Historic Period

https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/sn00b2449

The open oak woodlands described in the accounts of Spanish explorers were in large part created by land use practices of the California Indians, particularly burning. Extensive ethnographic evidence documents widespread use of fire by indigenous people to manipulate plants utilized for food, basketry, tools, clothing, and other uses. Fire helped maintain oak woodlands and reduce expansion of conifers where these forest types overlapped.